Activation is all you need

Activation functions

- What: Activation functions are mapping functions that take a single number and perform a certain fixed mathematical operation on it, generally inducing non-linearity.

- Why: They are used to flexibly squash the input through a function and pave the way recovering a higher-level abstraction structure. They partition the input space and regress towards the desired outcome.

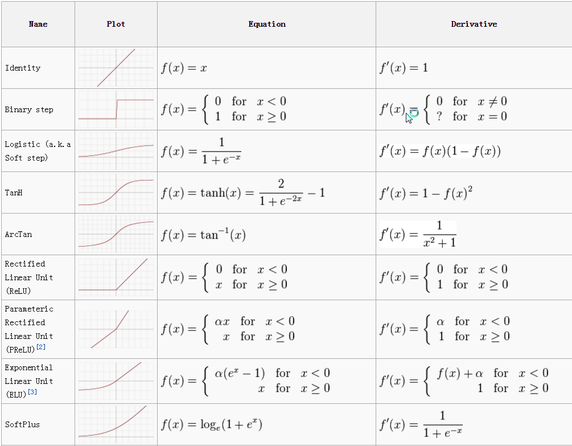

Cheatsheet

Sigmoid activation

Sigmoid takes a real-valued number and “squashes” it into a range between 0 and 1. In particular, large negative numbers become 0 and large positive numbers become 1. The sigmoid function has seen frequent use historically since it has a nice interpretation as the firing rate of a neuron: from not firing at all (0) to fully-saturated firing at an assumed maximum frequency (1). In practice, the sigmoid non-linearity has recently fallen out of favor and it is rarely ever used.

Drawbacks of sigmoid:

- Sigmoids saturate and kill gradients: A very undesirable property of the sigmoid neuron is that when the neuron’s activation saturates at either tail of 0 or 1, the gradient at these regions is almost zero. Recall that during backpropagation, this (local) gradient will be multiplied by the gradient of this gate’s output for the whole objective. Therefore, if the local gradient is very small, it will effectively “kill” the gradient and almost no signal will flow through the neuron to its weights and recursively to its data. Additionally, one must pay extra caution when initializing the weights of sigmoid neurons to prevent saturation. For example, if the initial weights are too large then most neurons would become saturated and the network will barely learn.

- Sigmoid outputs are not zero-centered: If the data received is not zero-centered, data would always be positive in case of sigmoid (ref: cheatsheet). During backpropagation, it makes the gradient on weights

wto become all positive, or all negative. This introduces undesirable zig-zag dynamics in the gradient update for weights. However, when batch-gradient descent is used, gradients are added up across a batch of data, with weights showing variable signs, mitigating this issue.

Rectified Linear Unit

The Rectified Linear Unit has become very popular in the last few years. It computes the function f(x)=max(0,x). In other words, the activation is simply thresholded at zero (ref: cheatsheet).

QnA on ReLU

Why is it better to have gradient 1 (ReLU) rather than arbitrarily small positive value (sigmoid)?

Because the gradient flows perfectly(100%) through the nodes during weight-updation and backpropagation, compared to a small percentage in sigmoid

The derivative of ReLU is exactly 0 when the input is smaller than 0, which causes the unit to never activate, rendering it forever useless. Possible explanations for why ReLU still works really good?

- Rectifier activation function allows a network to easily obtain sparse representations. For example, after uniform initialization of the weights, around 50% of hidden units continuous output values are real zeros, and this fraction can easily increase with sparsity-inducing regularization.

- Advantages of sparsity:

- Information disentangling: One of the claimed objectives of deep learning algorithms is to disentangle the factors explaining the variations in the data. A dense representation is highly entangled because almost any change in the input modifies most of the entries in the representation vector. Instead, if a representation is sparse it’ll be robust to small input changes. Sparse model creates an effect similar to regularization, where the main motive is to spread the weights rather than cluster around one particular node.

- Efficient variable-size representation: Different inputs may contain different amounts of information and would be more conveniently represented using a variable-size data-structure, which is common in computer representations of information. Varying the number of active neurons allows a model to control the effective dimensionality of the representation for a given input and the required precision.

- Linear separability: Sparse representations are also more likely to be linearly separable, or more easily separable with less non-linear machinery, simply because the information is represented in a high-dimensional space. Besides, this can reflect the original data format. In text-related applications, for instance, the original raw data is already very sparse.

The sparsity achieved in ReLU is similar to the vanishingly small gradients which vanish to values around 0. How is it advantageous for ReLU and a disadvantage to sigmoid?

Sigmoid is a bell curve with derivatives(gradients) going to 0 on both sides of the axes. For weight updation, usually many gradients are multiplied together, making the overall product very near to 0, giving the network no chance to recover. In case of ReLU, the gradient is +ve on one side of the axis, and some gradients going to zero on the other side of axis resulting in a few dead nodes. This gives the network a chance to recover since some gradients are positive.

What is the dying ReLU problem and solutions to combat that?

A “dead” ReLU always outputs the same value (zero as it happens, but that is not important) for any input. In turn, that means that it takes no role in discriminating between inputs. For classification, you could visualize this as a decision plane outside of all possible input data. Once a ReLU ends up in this state, it is unlikely to recover, because the function gradient at 0 is also 0, so gradient descent learning will not alter the weights.

Solution:

Leaky ReLUs are one attempt to fix the “dying ReLU” problem. Instead of the function being zero when x < 0, a leaky ReLU will instead have a small negative slope (of 0.01, or so)