Primer on convolution neural networks

- Introduction

- Background

- The Problem Space

- Inputs and Outputs

- Complete model

- Structure

- Training

- Hyperparameters

- Quiz time

- Activation Functions Cheat Sheet

- Rectified Linear Unit

- Pooling Layers

- Dropout Layers

- Network in Network Layers (1x1 convolution)

- Brain/ Neuron view of CONV layer

- CNNs over NNs

- Case study

- References

Introduction

Sounds like a weird combination of biology and math with a little CS sprinkled in, but these networks have been some of the most influential innovations in the field of computer vision. The classic and arguably most popular use case of these networks is for image processing, and recently applied to Natural Language Processing

Background

-

The first successful applications of ConvNets was by Yann LeCun in the 90’s, he created something called LeNet, that could be used to read hand written number

(source: giphy)

- In 2010 the Stanford Vision Lab released ImageNet. Image net is data set of 14 million images with labels detailing the contents of the images.

- The first viable example of a CNN applied to Image was AlexNet in 2012

The Problem Space

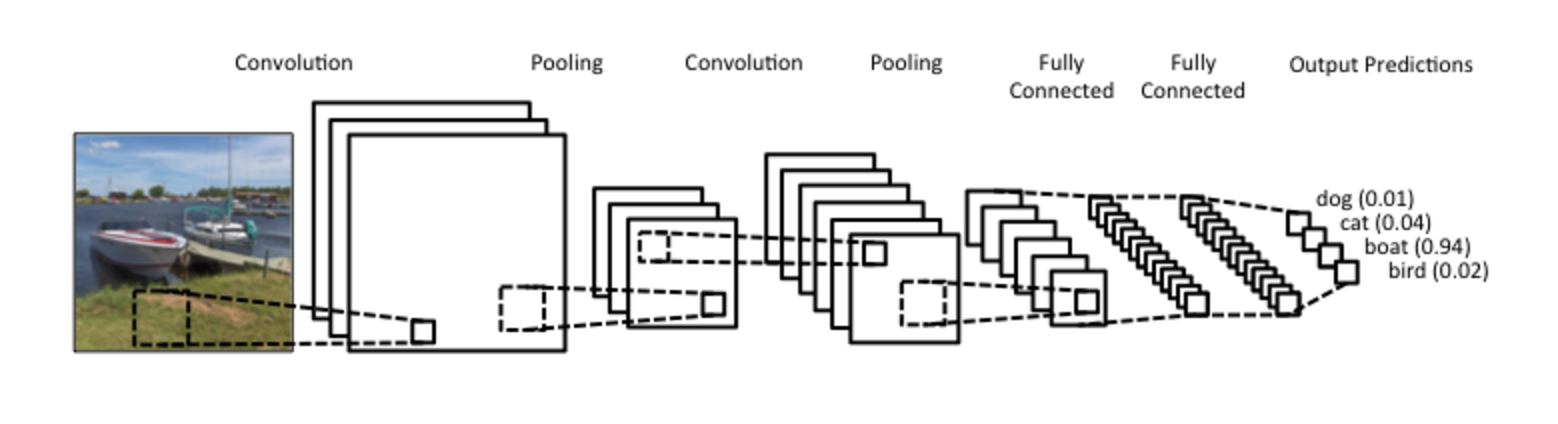

Image classification is the task of taking an input image and outputting a class (a cat, dog, etc) or a probability of classes that best describes the image. So, this turns out to be in Supervised Classification space. The whole network expresses a single differentiable score function: from the raw image pixels on one end to class scores at the other

(source: sourcedexter)

Inputs and Outputs

Unlike a regular Neural Network, the layers of a ConvNet have neurons arranged in 3 dimensions: width x height x depth. Each of these numbers is given a value from 0 to 255 which describes the pixel intensity at that point.

Complete model

(source: clarifai)

Structure

We use three main types of layers to build ConvNet architectures: Convolutional Layer, Pooling Layer, and Fully-Connected Layer. We will stack these layers to form a full ConvNet architecture. We’ll take the example of CIFAR-10 for better understanding.

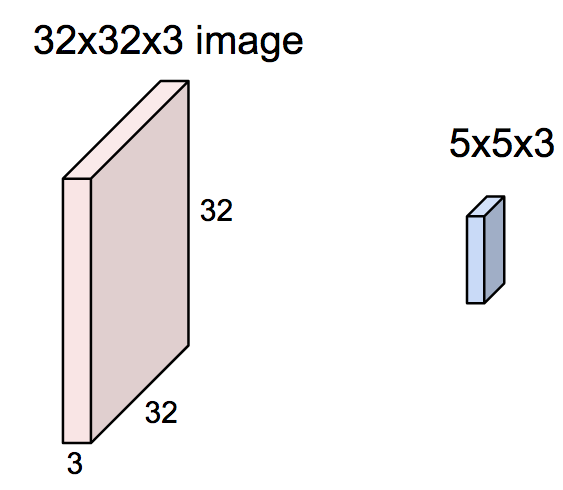

Input

INPUT [32x32x3] will hold the raw pixel values of the image, in this case an image of width 32, height 32, and with three color channels R,G,B.

Convolution (Math part)

-

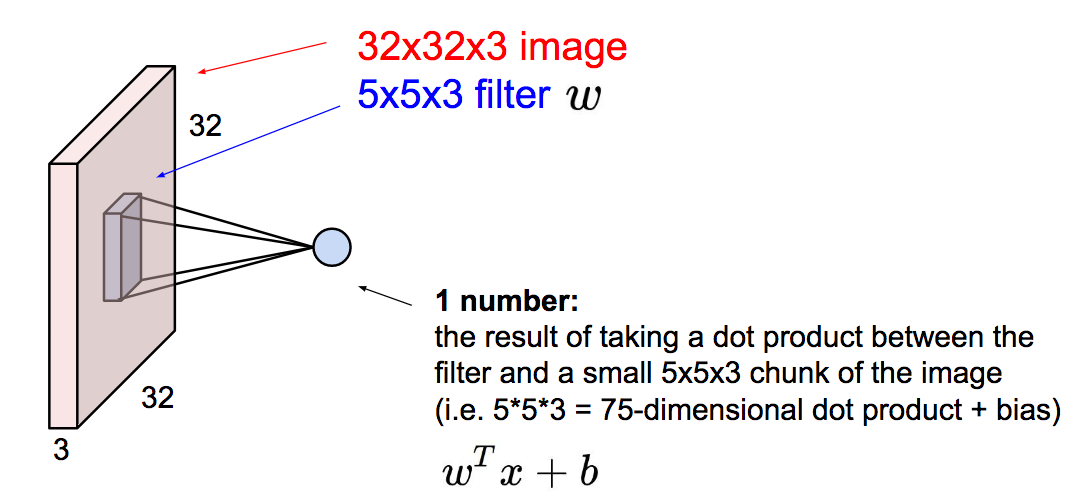

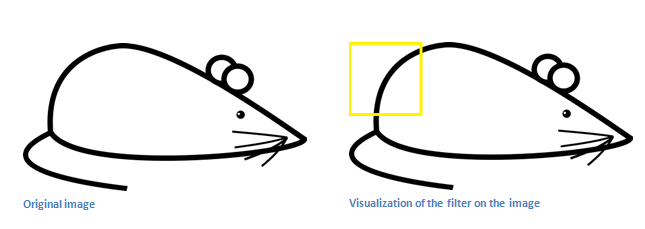

Imagine a flashlight that is shining over the top left of the image. Let’s say that the light this flashlight shines covers a 5 x 5 area. Now, let’s imagine this flashlight sliding across all the areas of the input image. In machine learning terms, this flashlight is called a filter or neuron or kernel and the region that it is shining over is called the receptive field. The filter is an array of numbers, where the numbers are called weights or parameters. The filter is randomly initialized at the start, and is learnt overtime by the network.

NOTE : Depth of this filter has to be the same as the depth of the input (this makes sure that the math works out), so the dimensions of this filter is 5 x 5 x 3.

(source: Andrej Karpathy)

-

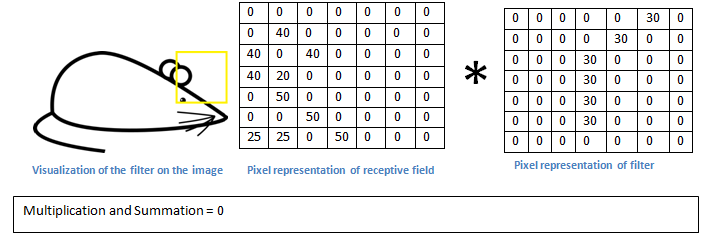

Lets take the first position of the filter for example, it would be at the top left corner. As the filter is sliding, or convolving, around the input image, it is multiplying the values in the filter with the original pixel values of the image (aka computing element wise multiplications).

-

Element wise multiplication : Filter and the receptive field in this example are (5 x 5 x 3) respectively, which has 75 multiplications in total. These multiplications are all summed up to have a single number. Remember, this number is just representative of when the filter is at the top left of the image. Now, we repeat this process for every location on the input volume. (Next step would be moving the filter to the right by 1 unit, then right again by 1, and so on). Every unique location on the input volume produces a number.

(source: Andrej Karpathy)

-

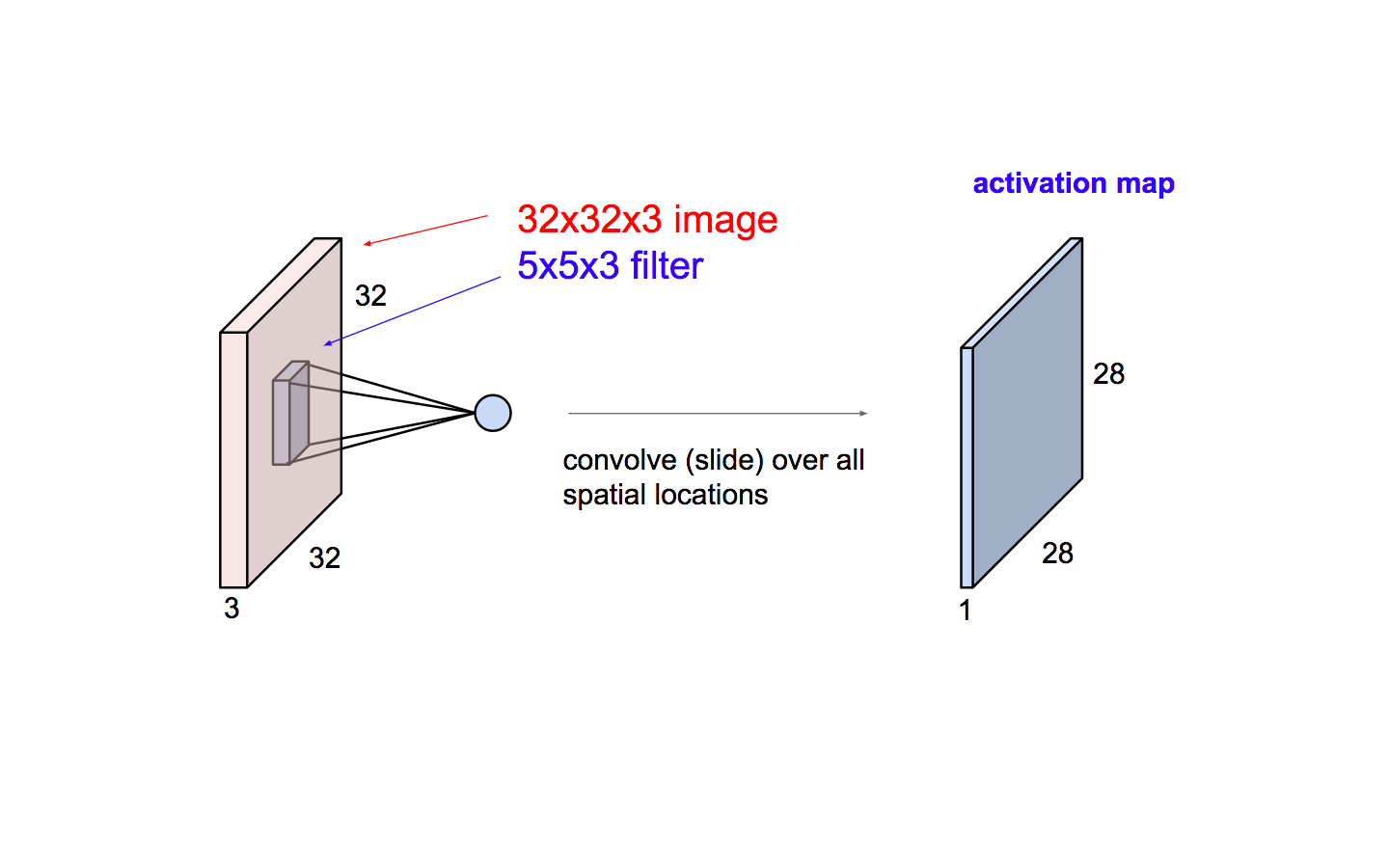

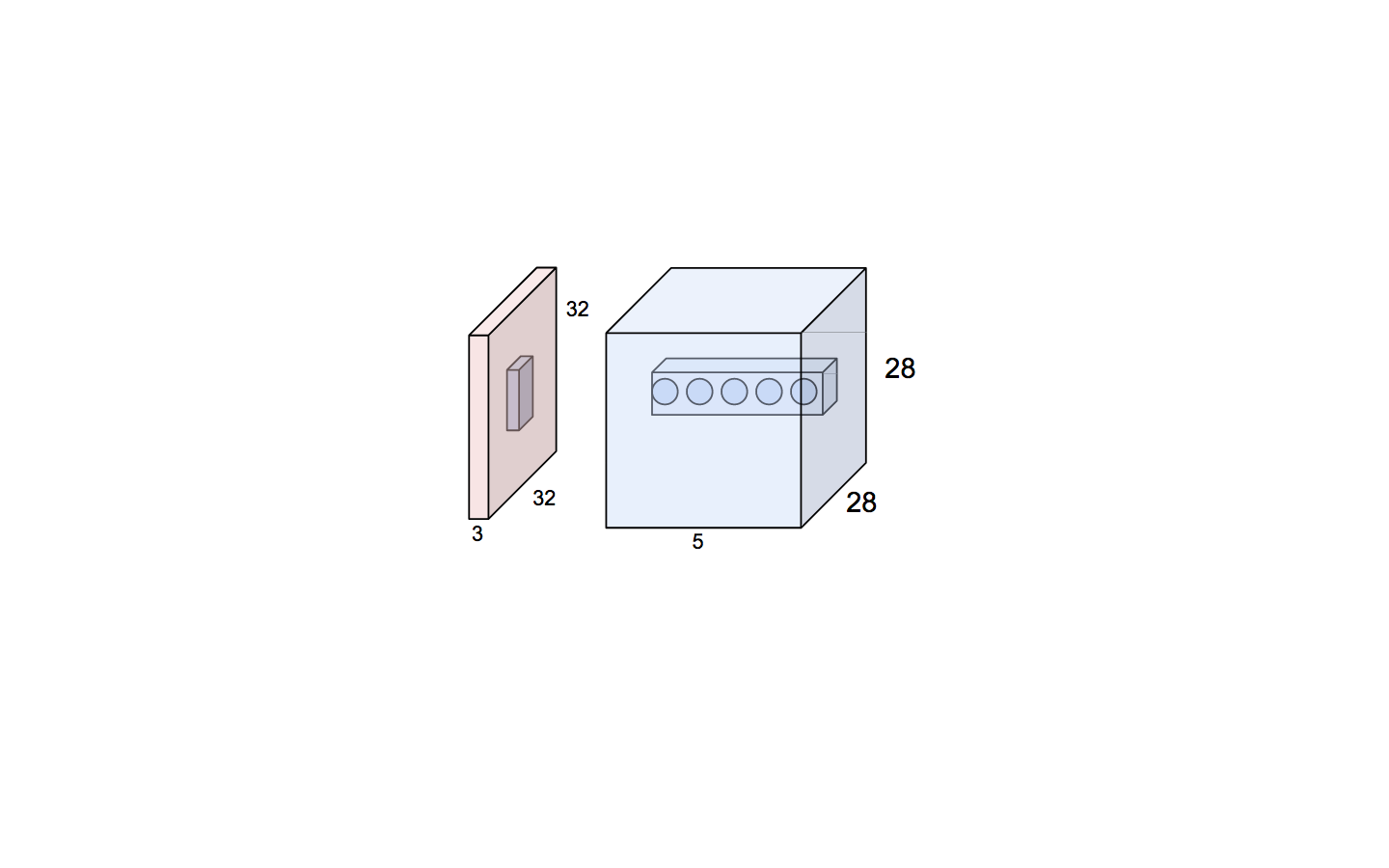

After sliding the filter over all locations, we are left with 28 x 28 x 1 array of numbers, which are called the activation map or feature map.

(source: Andrej Karpathy)

-

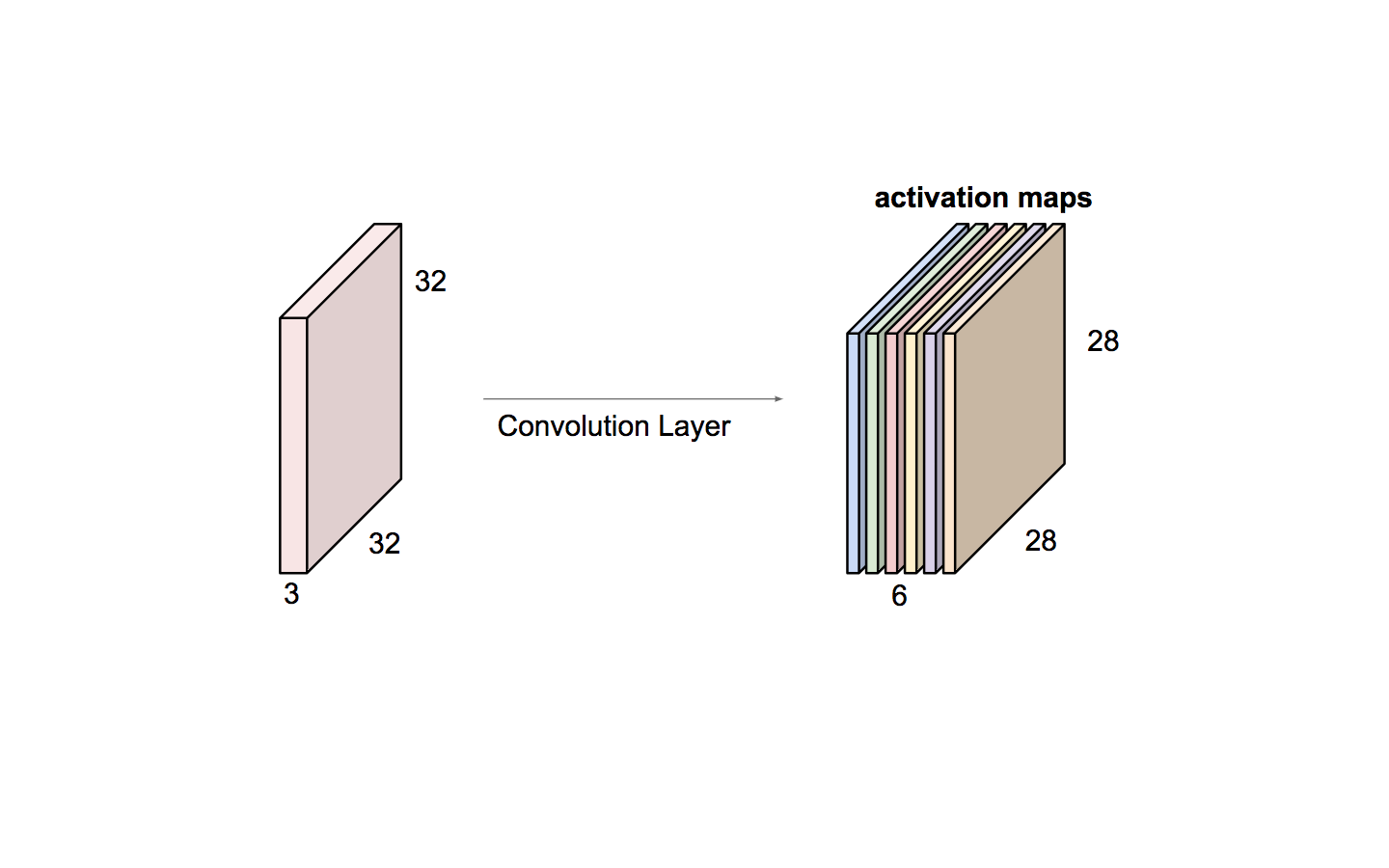

Now, we will have an entire set of filters in each CONV layer (e.g. 6 filters), and each of them will produce a separate 2-dimensional activation map. We will stack these activation maps along the depth dimension and produce the output volume ( 28 x 28 x 6)

(source: Andrej Karpathy)

-

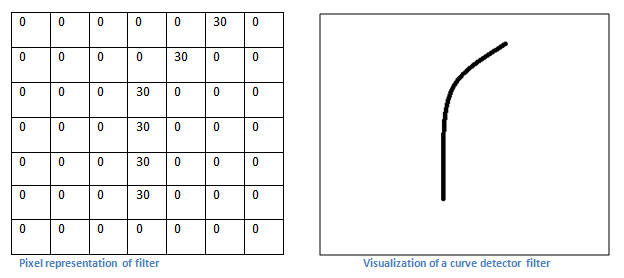

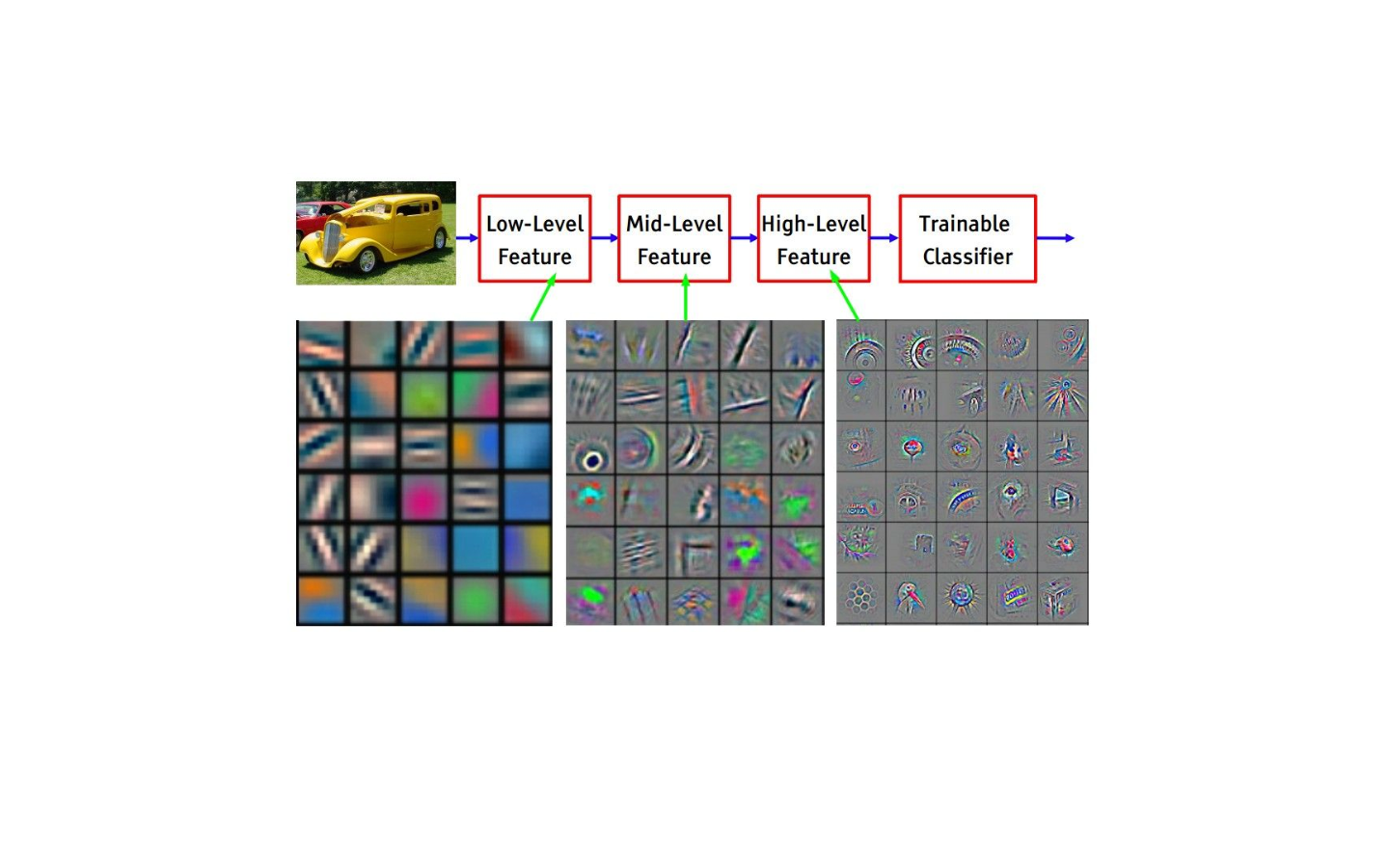

Intuitively, the network will learn filters that activate when they see some type of visual feature such as an edge of some orientation or a blotch of some color on the first layer, or eventually entire honeycomb or wheel-like patterns on higher layers of the network

Convolution (High level perscpective)

Let’s say our first filter is 7 x 7 x 3 and is going to be a curve detector. As a curve detector, the filter will have a pixel structure in which there will be higher numerical values along the area that is a shape of a curve

(source: adeshpande)

When we have this filter at the top left corner of the input volume, it is computing multiplications between the filter and pixel values at that region.

Now let’s take an example of an image that we want to classify, and let’s put our filter at the top left corner.

![]()

(source: adeshpande)

Basically, in the input image, if there is a shape that generally resembles the curve that this filter is representing, then all of the multiplications summed together will result in a large value! Now let’s see what happens when we move our filter.

(source: adeshpande)

The value is much lower! This is because there wasn’t anything in the image section that responded to the curve detector filter. This is just a filter that is going to detect lines that curve outward and to the right. We can have other filters for lines that curve to the left or for straight edges. The more filters, the greater the depth of the activation map, and the more information we have about the input volume.

Now when you apply a set of filters on top of previous activation map (pass it through the 2nd conv layer), the output will be activations that represent higher level features. Types of these features could be semicircles (combination of a curve and straight edge) or squares (combination of several straight edges). As you go through the network and go through more CONV layers, you get activation maps that represent more and more complex features. By the end of the network, you may have some filters that activate when there is handwriting in the image, filters that activate when they see pink objects, etc.

(source: Andrej Karpathy)

Fully connected layer

This layer basically takes an input volume (whatever the output is of the CONV or ReLU or POOL layer preceding it) and outputs an N dimensional vector where N is the number of classes that the program has to choose from. For example, if you wanted a digit classification program, N would be 10 since there are 10 digits. Each number in this N dimensional vector represents the probability of a certain class.

Training

-

Forward pass

- Take a training image which as we remember is a 32 x 32 x 3 array of numbers and pass it through the whole network. On our first training example, since all of the weights or filter values were randomly initialized, the output will probably be something like [.1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1 .1], basically an output that doesn’t give preference to any number in particular. The network, with its current weights, isn’t able to look for those low level features or thus isn’t able to make any reasonable conclusion about what the classification might be.

-

Loss function

-

Let’s say for example that the first training image inputted was a 3. The label for the image would be [0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0]. A loss function can be defined in many different ways but a common one used in classification is Cross Entropy often called as LogLoss.

-

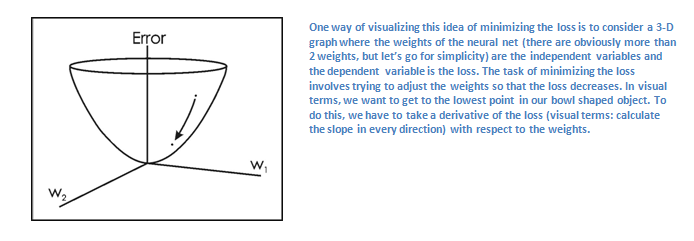

As you can imagine, the loss will be extremely high for the first couple of training images. Now, let’s just think about this intuitively. We want to get to a point where the predicted label (output of the ConvNet) is the same as the training label (This means that our network got its prediction right). In order to get there, we want to minimize the amount of loss we have. Visualizing this as just an optimization problem in calculus, we want to find out which inputs (weights in our case) most directly contributed to the loss (or error) of the network.

-

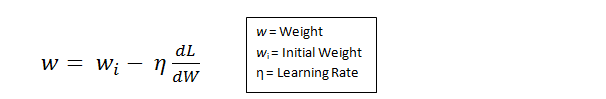

This is the mathematical equivalent of a dL/dW where W are the weights at a particular layer.

-

-

Backward pass

- Perform backward pass through the network, which is determining which weights contributed most to the loss and finding ways to adjust them so that the loss decreases.

-

Weight update

-

We take all the weights of the filters and update them so that they change in the opposite direction of the gradient.

-

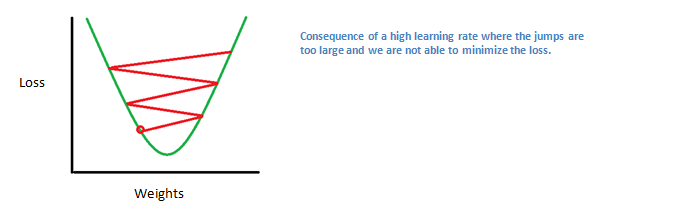

A high learning rate means that bigger steps are taken in the weight updates and thus, it may take less time for the model to converge on an optimal set of weights. However, a learning rate that is too high could result in jumps that are too large and not precise enough to reach the optimal point.

-

The process of forward pass, loss function, backward pass, and parameter update is one training iteration. The program will repeat this process for a fixed number of iterations for each set of training images (commonly called a batch). Once you finish the parameter update on the last training example, hopefully the network should be trained well enough so that the weights of the layers are tuned correctly.

Hyperparameters

-

Stride

-

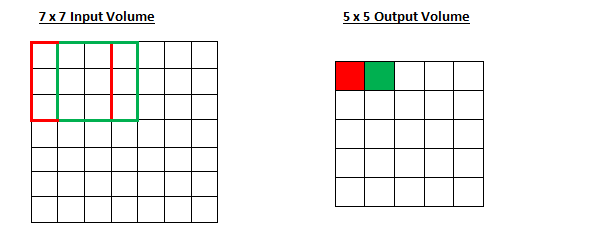

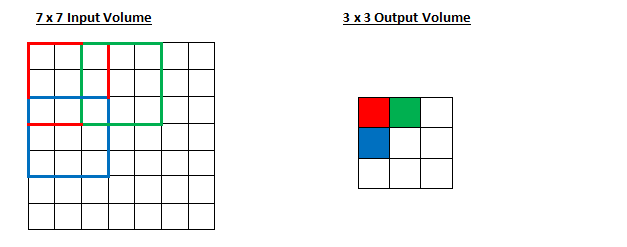

The amount by which the filter shifts is the stride. Stride is normally set in a way so that the output volume is an integer and not a fraction.

-

Let’s look at an example. Let’s imagine a 7 x 7 input volume, a 3 x 3 filter and a stride of 1.

Stride of 2 :

-

The receptive field is shifting by 2 units now and the output volume shrinks as well. Notice that if we tried to set our stride to 3, then we’d have issues with spacing and making sure the receptive fields fit on the input volume.

-

-

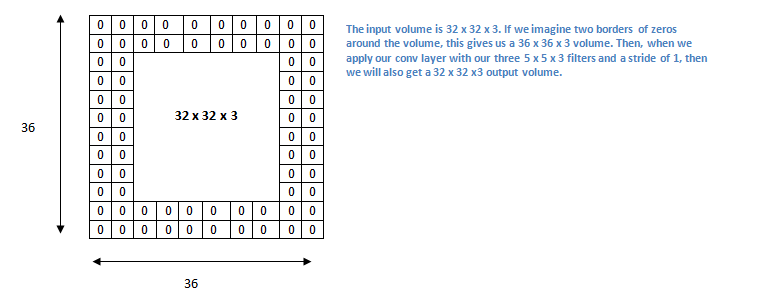

Padding

- Motivation:

What happens when you apply three 5 x 5 x 3 filters to a 32 x 32 x 3 input volume? The output volume would be 28 x 28 x 3. Notice that the spatial dimensions decrease. As we keep applying CONV layers, the size of the volume will decrease faster than we would like. In the early layers of our network, we want to preserve as much information about the original input volume so that we can extract those low level features. If we want to apply the same CONV layer, but we want the output volume to remain 32 x 32 x 3 ? Zero-padding comes to the rescue -

Zero padding pads the input volume with zeros around the border.

-

The formula for calculating the output size for any given CONV layer is

where O is the output height/length, W is the input height/length, K is the filter size, P is the padding, and S is the stride

- Motivation:

Quiz time

Input volume: 32x32x3

10 5x5 filters with stride 1, pad 2

Output volume size: ?

Number of parameters in this layer?

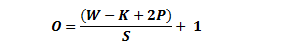

Activation Functions Cheat Sheet

Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU)

After each CONV layer, it is convention to apply a nonlinear layer (or activation layer) immediately afterward.The purpose of this layer is to introduce non-linearity to a system that basically has just been computing linear operations during the CONV layers (just element wise multiplications and summations).

It also helps to alleviate the vanishing gradient problem, which is the issue where the lower layers of the network train very slowly because the gradient decreases exponentially through the layers

ReLU layer applies the function f(x) = max(0, x) to all of the values in the input volume. In basic terms, this layer just changes all the negative activations to 0.

Rectified Linear Units Improve Restricted Boltzmann Machines

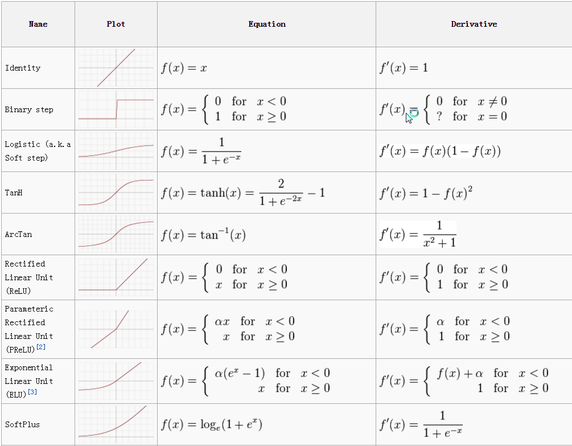

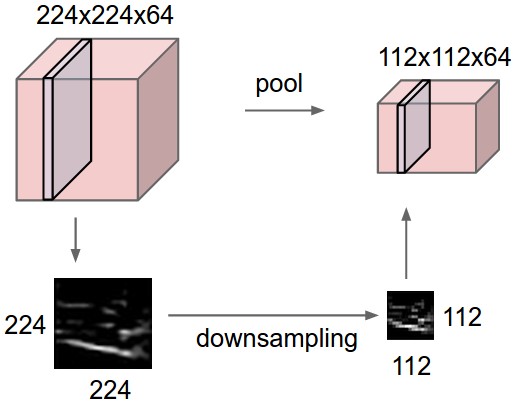

Pooling Layers

It is also referred to as a down-sampling layer. In this category, there are also several layer options, with max-pooling being the most popular. This basically takes a filter (normally of size 2x2) and a stride of the same length. It then applies it to the input volume and outputs the maximum number in every subregion that the filter convolves around.

(source: Andrej Karpathy)

Other options for pooling layers are average pooling and L2-norm pooling.

The intuitive reasoning behind this layer is that once we know that a specific feature is in the original input volume (there will be a high activation value), its exact location is not as important as its relative location to the other features. As you can imagine, this layer drastically reduces the spatial dimension (the length and the width change but not the depth) of the input volume. This serves two main purposes. The first is that the amount of parameters or weights is reduced by 75%, thus lessening the computation cost. The second is that it will control overfitting.

Dropout Layers

This layer “drops out” a random set of activations in that layer by setting them to zero.

What are the benefits of such a simple and seemingly unnecessary and counterintuitive process?

It forces the network to be redundant. The network should be able to provide the right classification or output for a specific example even if some of the activations are dropped out. It makes sure that the network isn’t getting too “fitted” to the training data and thus helps alleviate the overfitting problem

Dropout: A Simple Way to Prevent Neural Networks from Overfitting

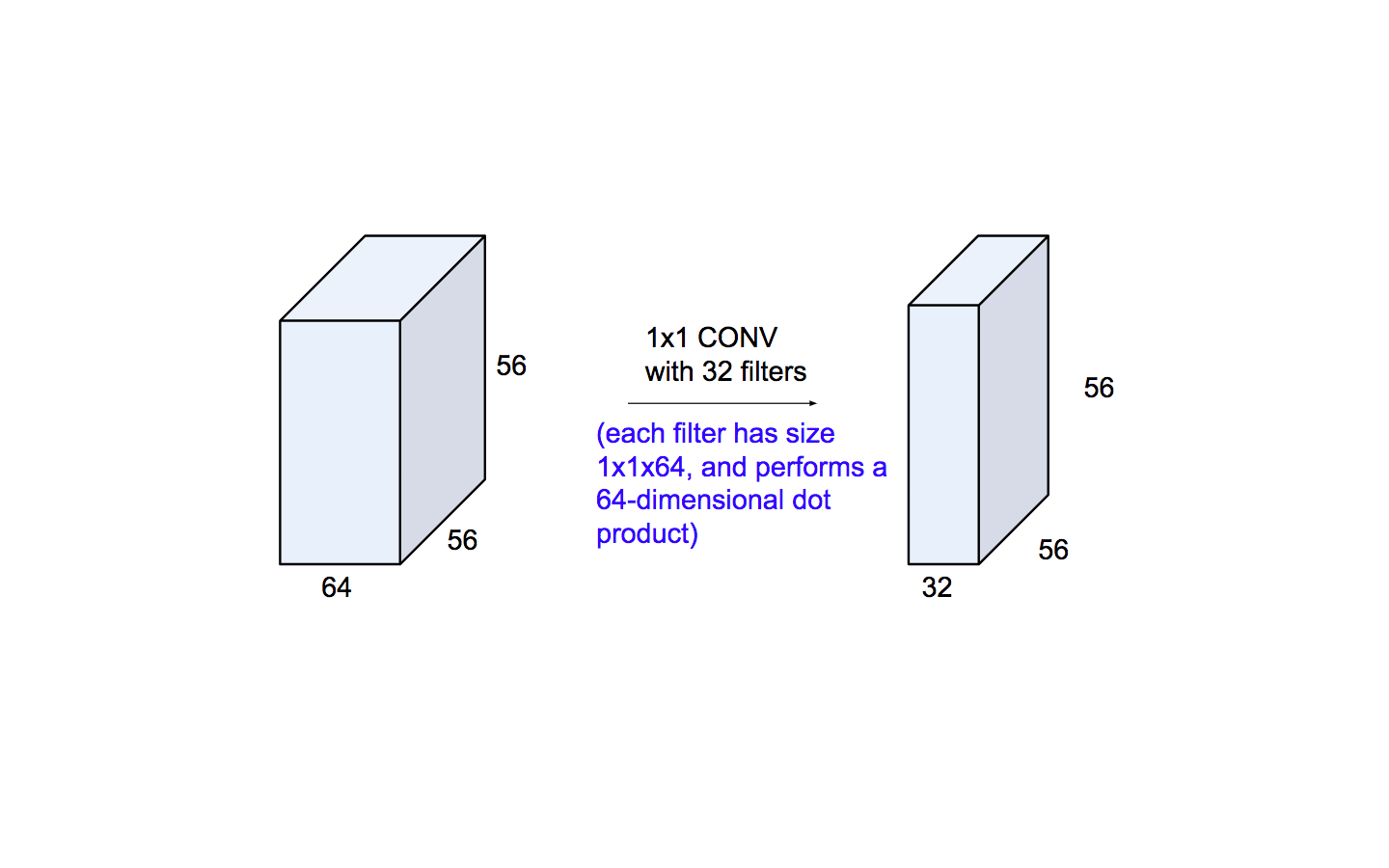

Network in Network Layers (1x1 convolution)

Now, at first look, you might wonder why this type of layer would even be helpful since receptive fields are normally larger than the space they map to. However, we must remember that these 1x1 convolutions span a certain depth, so we can think of it as a 1 x 1 x N convolution where N is the number of filters applied in the layer. They are also used as a bottle-neck layer which internally is used to decrease the number of parameters to be trained, and hence reduces the total computation time.

Dimensionality reduction:

- Height and Width : Max-pooling

- Depth : 1x1 convolution

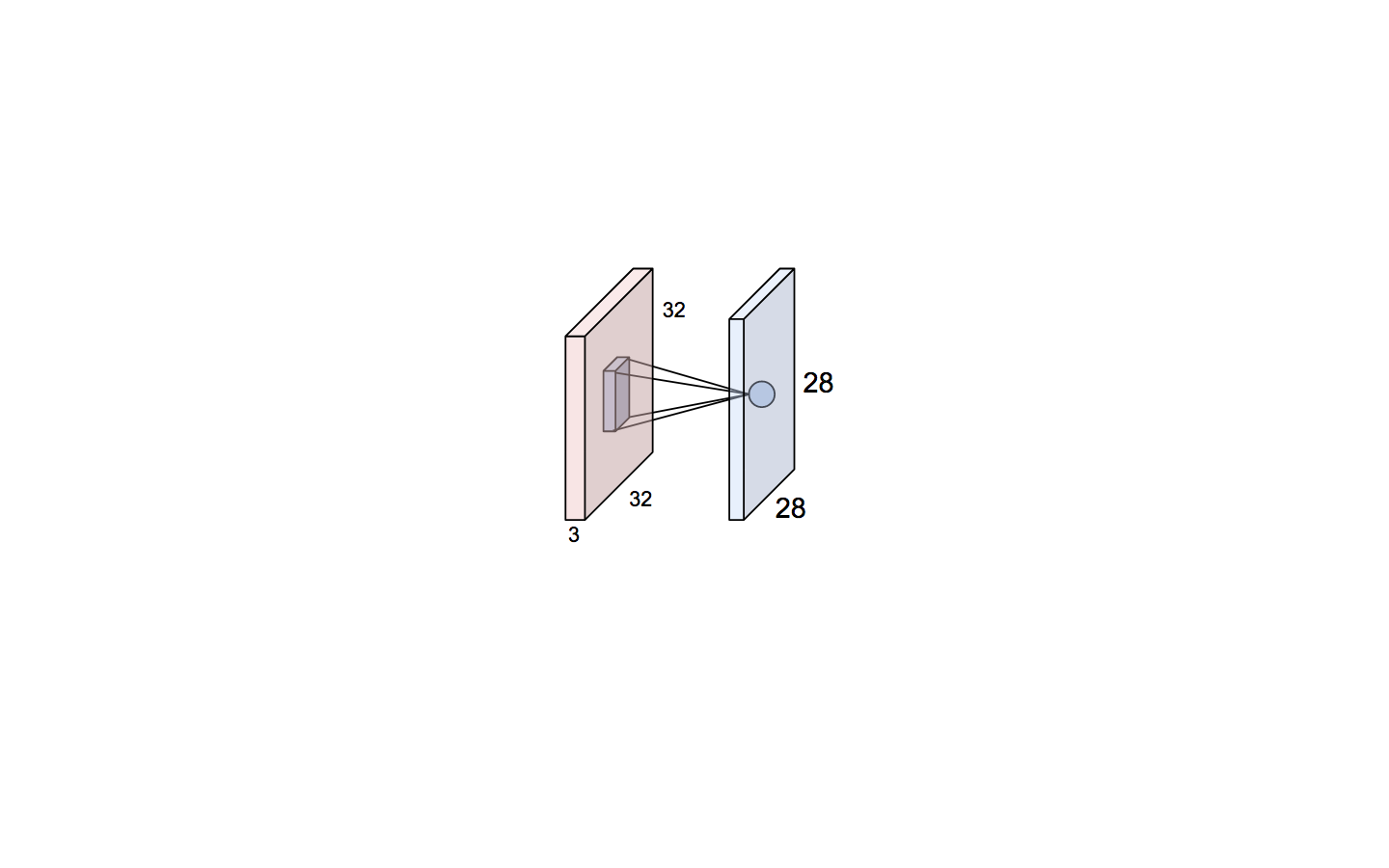

Brain/ Neuron view of CONV layer

Suppose we have an input of 32 x 32 x 3 and we convolve a filter of size 5 x 5 x 3, we get the below picture

An activation map is a 28 x 28 sheet of neuron outputs where in :

- Each is connected to a small region in the input

- All of them share parameters

We convolve 5 filters of size 5x5x3 and get 28x28x5 output. Each neuron shares parameters with its siblings in the same filter, but does’t share parameters across the depth (other filters)

But each neuron across the depth of the activation map looks at the same receptive field in the input, but have different parameters/filters.

CNNs over NNs

- Parameter sharing : A feature detector (such as a vertical edge detector) that’s useful in one part of the image is probably useful in another part of the image. Probability of having different data distributions in different parts of same image is very low.

- Sparsity of connections : In each layer, each output value depends only on a small number of inputs, compared to NNs where a single output value depends on every input value since it is fully connected.

Reasons above allow CNNs to have lot few parameters which allows it to be trained on smaller training sets and less prone to overfitting. CNNs are good at capturing translation invariance (shift by a few pixels shouldn’t matter the prediction)

Case Study

There are several architectures in the field of Convolutional Networks that have a name. The most common are:

- LeNet. The first successful applications of Convolutional Networks were developed by Yann LeCun in 1990’s. Of these, the best known is the LeNet architecture that was used to read zip codes, digits, etc.

- AlexNet. The first work that popularized Convolutional Networks in Computer Vision was the AlexNet, developed by Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever and Geoff Hinton. The AlexNet was submitted to the ImageNet ILSVRC challenge in 2012 and significantly outperformed the second runner-up (top 5 error of 16% compared to runner-up with 26% error). The Network had a very similar architecture to LeNet, but was deeper, bigger, and featured Convolutional Layers stacked on top of each other (previously it was common to only have a single CONV layer always immediately followed by a POOL layer).

- ZF Net. The ILSVRC 2013 winner was a Convolutional Network from Matthew Zeiler and Rob Fergus. It became known as the ZFNet (short for Zeiler & Fergus Net). It was an improvement on AlexNet by tweaking the architecture hyperparameters, in particular by expanding the size of the middle convolutional layers and making the stride and filter size on the first layer smaller.

- GoogLeNet. The ILSVRC 2014 winner was a Convolutional Network from Szegedy et al. from Google. Its main contribution was the development of an Inception Module that dramatically reduced the number of parameters in the network (4M, compared to AlexNet with 60M). Additionally, this paper uses Average Pooling instead of Fully Connected layers at the top of the ConvNet, eliminating a large amount of parameters that do not seem to matter much. There are also several followup versions to the GoogLeNet, most recently Inception-v4.

- VGGNet. The runner-up in ILSVRC 2014 was the network from Karen Simonyan and Andrew Zisserman that became known as the VGGNet. Its main contribution was in showing that the depth of the network is a critical component for good performance. Their final best network contains 16 CONV/FC layers and, appealingly, features an extremely homogeneous architecture that only performs 3x3 convolutions and 2x2 pooling from the beginning to the end. Their pretrained model is available for plug and play use in Caffe. A downside of the VGGNet is that it is more expensive to evaluate and uses a lot more memory and parameters (140M). Most of these parameters are in the first fully connected layer, and it was since found that these FC layers can be removed with no performance downgrade, significantly reducing the number of necessary parameters.

- ResNet. Residual Network developed by Kaiming He et al. was the winner of ILSVRC 2015. It features special skip connections and a heavy use of batch normalization. The architecture is also missing fully connected layers at the end of the network. The reader is also referred to Kaiming’s presentation (video, slides), and some recent experiments that reproduce these networks in Torch. ResNets are currently by far state of the art Convolutional Neural Network models and are the default choice for using ConvNets in practice (as of May 10, 2016). In particular, also see more recent developments that tweak the original architecture from Kaiming He et al. Identity Mappings in Deep Residual Networks (published March 2016).